Because of the routines we follow, we often forget that life is an ongoing adventure… and the sooner we realize that, the quicker we will be able to treat life as art: to bring all our energies to each encounter, to remain flexible enough to notice and admit when what we expected to happen did not happen. We need to remember that we are created creative and can invent new scenarios as frequently as they are needed.

Maya Angelou, Wouldn’t Take Nothing for My Journey Now

Neema* was a 43-year-old refugee and mother of five from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Every week she rode the city bus for half an hour to meet me for English lessons at the Department of Human Services in Portland, Oregon. Regardless of the time of year (there are really only two seasons in Portland: an overcast drizzle of fall/winter/spring and a glorious, sun-filled summer), she wore striking, colorful wrap dresses traditional to her African origin paired with Adidas sandals and socks. She was shy, spoke in a whisper, and entered the government building lobby with noticeable hesitation and uncertainty. On most days, the lobby was a sad microcosm of poverty and hardship; this is where people requested government assistance, but also where the desperate and destitute gathered in hopes of securing other life extensions. It was often chaotic, loud, and smelled; not the most welcoming of environments for those from distant lands struggling to find their place, too, in America.

But on the other side of this lobby, I had a secure, private classroom at my disposal, and this is where I came, week after week as an ESL specialist, to welcome and teach those displaced by war, conflict, and desperate situations. Each week I made an effort to create some sort of safe space for learning and opportunity to take place. Students were referred to me by government caseworkers in the form of an ID number, name, and contact information, but it was up to me to translate that into a human connection.

Neema was illiterate; she had never learned how to hold a pencil or write her name. She was familiar with some English: most of the alphabet, numbers one through ten, and basic greetings. She spoke Swahili with her family, but the time had come for her to gain employment in her new home country. Her government file told me she had come to the US after fleeing civil turmoil in her native DRC. Her body language and my own research on the terrors endured by Congolese women led me to make additional harrowing conclusions. But now she was here, in Portland, with mostly grown children and she was settled enough to maintain a job. How would we even begin?

The Body Keeps the Score

In his fascinating and empowering book The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, Dutch psychiatrist and author Dr. Bessel Van der Kolk provides a framework for understanding trauma and its debilitating effects on both individuals and society at large. As he succinctly puts it, “Trauma robs you of the feeling you are in charge of yourself” (205). It is an impediment to freedom at its most basic existence: within our own minds and bodies. How we help and work with traumatized individuals is multi-faceted but increasingly essential in our interconnected world. Starting with the basic emotional needs of individuals – human beings, one at a time – is a tangible path towards contributing to a healthier, more inclusive society. Here I’ve applied what I’ve learned from Dr. Van der Kolk’s book to the work I’ve done in English-language instruction for immigrants and refugees, specifically those exhibiting symptoms of trauma. This article is a first-attempt gathering of my observations, approaches, and hopes for a more inclusive, holistic future.

The Truth About Trauma

“Trauma constantly confronts us with our fragility and with man’s inhumanity to man, but also with our extraordinary resilience.”

Dr. Bessel Van der Kolk

Entering that chaotic lobby at the Department of Human Services, resilience – albeit battered and apprehensive – is what showed on the faces of the students who came to me for English language instruction during my time as an ESL specialist for an immigrant and refugee-centered nonprofit in Portland, Oregon. Like my other refugee students who were displaced from their homes and families by war and instability in countries like Ukraine, Myanmar, and Afghanistan, Neema met with me after I had conducted a translator-assisted phone screening to assess her needs and abilities. Students often sound reticent and uncomfortable on these phone calls, but with gentleness and determination, the first meeting is set up and realized. Each time a new student timidly arrived at that grim government lobby, I made whole-body efforts to greet them immediately, warm eye contact and a genuine smile leading the way forward. I took the time to let them know that one, they were both expected and welcomed and two, I saw them as human beings – not case numbers or quotas – in the present. Dr. Van der Kolk explains, “Being traumatized is not just an issue of being stuck in the past; it is just as much a problem of not being fully alive in the present” (223). My work with each traumatized student began before any grammar or spelling concept was introduced; it started with acknowledging their existence and their presence in the here and the now. Once greetings and schedules were established, we could begin language learning in the same holistic vein.

Traditional and systematic teaching approaches often fall short, especially when quantified markers of “successful outcomes” are the contractual goal. Learning and engagement struggle to take place when there are deeper, emotionally-driven impediments. Van der Kolk strikes at the heart of this when he observes, “Sadly, our educational system, as well as many of the methods that profess to treat trauma, tend to bypass this emotional-engagement system and focus instead on recruiting the cognitive capacities of the mind. Despite the well-documented effects of anger, fear, and anxiety on the ability to reason, many programs continue to ignore the need to engage the safety system of the brain before trying to promote new ways of thinking” (88). So if engaging the “safety system of the brain” is paramount to embarking on a positive and successful learning relationship, we as teachers must create conditions and environments where the student feels relaxed and safe. This starts with the aforementioned warm, welcoming disposition and manifests further in tone, body language and positioning, and one-on-one activities.

Initially, we can be deterred if we meet individuals who make this introduction and establishment of a learning routine “difficult” due to misinterpreted attitudes or a lack of interest. But these are opportunities to explore empathy as a verb and try to understand their root causes: “It is much more productive to see aggression or depression, arrogance or passivity as learned behaviors: somewhere along the line, the patient came to believe that he or she could survive only if he or she was tough, invisible, or absent, or that is was safer to give up” (Van der Kolk, 280). I found that employing very fundamental, holistic approaches (leading with warmth and gentleness, attention to tone and body language, creating a calm environment, etc.) calibrated to individual students was foundational to making an initial connection and maintaining a relationship, especially with the “difficult” ones; it was not until reading The Body Keeps the Score that I finally understood the science behind these methods.

The Science Behind Trauma

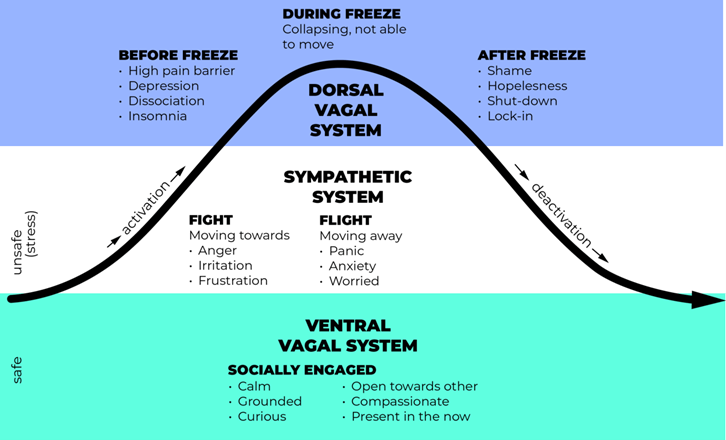

The nervous system, the limbic system, the reptilian brain: I’d certainly heard of these things but what they had to do with my line of work was not something I pondered in depth until recently with my reading. Uncovering the functions and manifestations of these components that make up our human bodies and brains, I felt at once enlightened and also affirmed in my approaches and methods. In order to best help those impacted by trauma, we should make an effort to understand the science behind our feelings and our body’s responses. Beginning with our brain and nervous system – specifically how these systems interpret our experiences and environments – we can learn how to effectively work with and grow from trauma’s debilitating effects. Van der Kolk explains how trauma-induced changes show in our bodies: “After trauma, the world is experienced with a different nervous system that has an altered perception of risk and safety… ‘neuroception’ is a term used to describe the capacity to evaluate relative danger and safety in one’s environment. When we try to help people with faulty neuroception, the great challenge is finding ways to reset their physiology, so that their survival mechanisms stop working against them. This means helping them to respond appropriately to danger but, even more, to recover the capacity to experience safety, relaxation, and true reciprocity” (82).

After that first meeting with Neema, I continued my gentle approach week after week: with a warm smile and eye contact that said “Welcome” before anything came out of my mouth. “Neema, I am so happy you are here,” I said each time while emphasizing the meaning of my words with gentle but exaggerated gestures and more warmth from smiling. Seeing our students, saying their name, and acknowledging the efforts they took to be present are all such simple interactions but crucial for establishing a learning relationship based on trust and familiarity. Each week I wanted Neema, and all my students, to know that with me they were safe and their presence was noticed and valued. That they are noticed and valued.

Creating the Space, Inside and Out

Throughout his book, Van der Kolk emphasizes the combination of both a top-down and a bottom-up approach in working with traumatized individuals, “top-down” meaning engaging our advanced frontal lobe (rational brain) as well as a “bottom-up” approach that targets our more primitive, emotional brain (the reptilian brain and the limbic system/mammalian brain). While traditional adult-centric learning methods mostly focus on delivering information to the rational brain (top-down), emphasis must be made on the bottom-up approach when working with traumatized individuals. This can be done by focusing on the body and its innate rhythmic functions governed by our nervous system (how our body regulates its functions). As Van der Kolk succinctly puts it, our rational brain is concerned with the world outside us, and the emotional brain is concerned with everything that happens in us (55-56). If there is unrest and discomfort within us, we cannot effectively process what is outside of us, including learning new information.

Bottom-up approaches target the vagus nerve, a key part of our parasympathetic (“with feelings”) nervous system that carries signals between our brain, heart, lungs, and digestive organs. The Polyvagal (“many-branched vagus”) Theory, introduced by American psychologist and neuroscientist Stephen Porges in 1994, proposes that “the evolution of the mammalian autonomic nervous system provides the neurophysiological substrates for adaptive behavioral strategies. It further proposes that physiological states limit the range of behavior and psychological experience” (Porges). In more simplistic, poetic terms, the vagus nerve registers heartbreak and gut-wrenching feelings. “When a person becomes upset, the throat gets dry, the voice becomes tense, the heart speeds up, and respiration becomes rapid and shallow,” Van der Kolk summarizes. “The Polyvagal Theory provides us with a more sophisticated understanding of the biology of safety and danger, one based on the subtle interplay between the visceral experiences of our own bodies and the voices and faces of the people around us. It explains why a kind face or a soothing tone of voice can dramatically alter the way we feel. It clarifies why knowing that we are seen and heard by important people in our lives can make us feel calm and safe, and why being ignored or dismissed can precipitate rage reactions or mental collapse. It helps us understand why focused attunement with another person can shift us out of disorganized and fearful states” (80). After establishing a warm and welcomed rapport, my next objective as an ESL specialist was to transfer my effort and attention to bottom-up breath work (which calms the nervous system) related to our purpose: learning and practicing language.

The Breath of Language

Breath is essential to language; if there is no breath, there are no words. With someone like Neema, who had little to no educational background, I approached our lessons with a bottom-up mindset, focusing on rhythm and repetition to create a game of familiarity with what English is supposed to sound like.

Simple exercises based on the sounds of the alphabet’s letters, the spelling of one’s name, and the melodic reciting of one’s phone number lent themselves beautifully to the incorporation of breath work; other efforts included synchronizing and mimicking phonetics, the humming and repetition of syllabic sounds, etc. While passively calming the vagus nerve with controlled inhalations and exhalations, we were also engaging in a game of language call and response that created a safe space to relax and learn. The calming effects of our controlled and gentle exercises allowed Neema to participate fully, engage with her body, and smile in the process. Even when she couldn’t recite her phone number correctly, she found pleasure in laughing at her mistakes while I mimicked her joy and encouraged her to try again.

With Neema and all my refugee students, I observed dual outcomes from exercises built on guided syllable articulation and pronunciation, rhythmic and melodic word repetition, song-based sentence structures: learning conversational English, but also the calming, therapeutic benefits of breathwork and motor regulation. I didn’t just teach semantics (word meaning) and syntax (word order); I helped refugees recover the use of trauma-affected basic self-regulation. I observed them slowly learning the English language, yes, but their success was only relative to the extent in which they were relaxed enough to be open to the information presented. When our lessons came to an end (either they found employment and/or their government benefits ended), my students were often very sad and expressed a desire to keep learning with me. Sure, they may have felt a fondness for me as their teacher, but I know the work we did served them holistically as much as it did intellectually. By actively participating and focusing on the breath and the language-centric activities I designed, their bodies self-regulated enough so they could let their guard down and enjoy learning.

Self-Confidence: The Ultimate Lesson

The role of play in building empowerment is evident at any stage of life. For traumatized individuals, it’s crucial to rebuilding an identity. Van der Kolk asserts that, “As long as people are hyper aroused or shut down [from their trauma], they cannot learn from experience. Even if they manage to stay in control, they become so uptight…that they are inflexible, stubborn, and depressed. Recovery from trauma involves the restoration of executive functioning and, with it, self-confidence and the capacity for playfulness and creativity” (207).

Week after week my lessons with Neema equipped her with the ability to recite (and eventually write) her personal information so she could apply to jobs suited for her capabilities. But more importantly, they made her feel comfortable and provided her a safe space to simply be engaged, with herself and with a trustworthy teacher, in the present. Slowly, she gained confidence, which was evident in her bright eyes and smile after reciting her phone number correctly or writing her full name. Working with people like Neema revealed to me the precious opportunities I had as an educator for refugees to impart not just knowledge and skills, but to acknowledge their being and (perhaps most crucial to our society) their belonging as well.

Van der Kolk observes that, “The critical challenge in a classroom setting is to foster reciprocity: truly hearing and being heard; really seeing and being seen by other people” (354). For refugees who have fled crises and continue to embody various states of trauma, being seen and acknowledged, face-to-face in the now, is an essential and holistic first step to assimilating and eventually thriving in a new society.

A Healthier, More Peaceful Society

As educators, we have a crucial role in helping our students imagine a better future for themselves. A healthy, thriving, peaceful society is only made up of the health and peace of the individuals in it. “Most of us are survivors of one thing or another, some much worse than others,” Van der Kolk asserts. “I want our society to know about trauma, and to really do all the things necessary so that people who grow up under extreme adverse conditions can develop a brain and a mind that can help them become full-fledged members of society.”

Creating safe learning environments and incorporating holistic approaches that establish a trusting, learning relationship is a crucial first step in what is often a long process of recovery for any student with trauma. It does not take expensive technology or an unlimited education budget, but deep understanding, empathy, and patience applied in the present moment. Start with seeing them in the now, gently, and go from there.

* Name changed to protect privacy

Works Cited:

Angelou, Maya. Wouldn’t Take Nothing for My Journey Now, pg 65-66, 1993.

Porges SW. “The polyvagal theory: new insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system.” Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Apr 2009.

Van der Kolk, Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, 2015.

Pingback: Mindfulness and the Year of Magical Reading – Allyson Abroad