Up high on the Janiculum hill of Rome, with breathtaking views of a city skyline filled with church cupolas and terracotta-colored buildings, sits San Pietro in Montorio. It’s one of a handful of churches in the city dedicated to Saint Peter, the apostle who is easily recognized in paintings and sculptures by the keys (to heaven, no less) that he carries with him at all times. Within the confines of this church, in a courtyard visible from the outside through a chained gate, lies arguably the most perfect representation of Italian Renaissance architecture: Donato Bramante’s Tempietto.

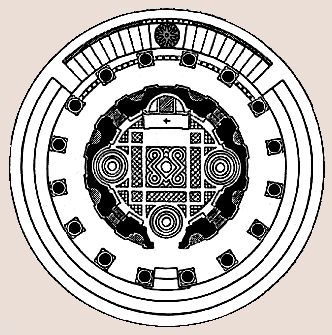

It’s called the “little temple,” as opposed to, say, a chapel or church, because its purpose is that of a marker for something, or somewhere, particularly sacred; this is especially similar to another type of religious building dedicated to holy sites of veneration called martyriams, which also happen to be circular in shape. Below the Tempietto’s altar is a circle in the ground that reveals a crypt-like space, decorated with elaborate carvings and sculptural details. It is precisely here – in another circle on the ground – that your attention is drawn to something of historic and spiritual significance: the site where Saint Peter, one of Jesus’ twelve apostles and the founder of the Catholic church, was crucified upside down (per his own request) by the Emperor Nero in circa 64 CE.

The Classical Origins of Renaissance Works

The circle and the Christian saint – two images that contain a wealth of symbolism in the Western world. So much of the Tempietto is composed of circles, a perfectly harmonious shape found in nature, and one that has been studied and explained in classical texts such as Vitruivius’ De architectura (c. 15 BCE). Circles and their meaning have been interpreted outside of nature, and have an especially pertinent significance in a piece of architecture like the Tempietto: that of the divine, of God, and eternity. Additionally, circles are easily found throughout Christian visual art; one need only glance at any painting of the Virgin Mary or Jesus, and there’s sure to be at least one perfectly round halo to be found.

Fused together by a meticulous and gifted architect, the Tempietto is pure poetry in stone. The small, rotund structure flawlessly accomplishes what all Italian Renaissance architecture aimed to do with its monumental cathedrals, peaceful chapels, and grand basilicas – synthesize the Christian faith with the aesthetic and intelligence of antiquity. Bringing these two seemingly opposite philosophies together in visual form is a main pillar of what the Italian Renaissance and humanism is all about. In bringing to light the accomplishments of antiquity, the Italians of the Renaissance were celebrating themselves and their own history, with remarkable achievements in architecture, painting, and sculpture. Turning away from the Middle Ages and an archaic, spiritually-based education system known as scholasticism, the Italian Renaissance produced innovations that were built on fact, not faith. Answers were found by means of experimentation in the real, natural world, not from explanations derived from biblical interpretation.

Why the sudden change? The invention of the printing press in 1440 certainly helped a great deal, bringing old texts, theories, and formulas into the hands of the masses, which accelerated learning and innovation at an exponential speed. One of the most significant rediscoveries found in these ancient texts were theories and discussions about geometry and its origin in the natural world. Mathematics, in addition to science and nature, is an essential component in the creation of Renaissance works. Its manifestation is in the symmetry and beauty we see when we are admiring the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel, or marveling at the Tempietto.

The trend towards embracing harmony and balance, particularly within architecture, found its revival with the first of the great Italian Renaissance architects, most notably Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti, the latter of whom regarded mathematics as the common ground between science and art. These men and their contemporaries are what gave the “rebirth” facet of the Renaissance its common understanding; they dove headfirst into the principles and geometry of Vitruvius and his treatise on architecture, De architectura (c. 15 BCE). By studying these ancient texts, Renaissance artists came to understand the intention behind imitating nature, and reproduced in their own works the intrinsic ratios and harmonies that exist in the living world around us and, indeed, even in our own bodies (consider the Vitruviun Man). Bursting the dogmatic bubble of scholasticism that held Western education in a tight grip for some 500 plus years, the Renaissance championed, for the first time in a long time, man and his achievements that were gained through curiosity, experimentation, and discovery. When we behold Renaissance art, craftsmanship and intelligence are on display, not mystery and insular contemplation.

Here, one felt no weight of the supernatural pressing on the human mind, demanding homage and allegiance. Humanity—with all its distinct capabilities, talents, worries, problems, possibilities—was the center of interest. It has been said that medieval thinkers philosophized on their knees, but, bolstered by the new studies, they dared to stand up and to rise to full stature.

The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy

We can see these innovations brought on by discovery in all the art forms of the Italian Renaissance. Like his contemporary Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarotti experimented with dissecting cadavers so that he could study and understand the form and function of human muscle, bone, and flesh. In doing so his renderings of figures, in both painting and sculpture, came to life. Forbidden by the church, this method of using the dead to study anatomy was commonly practiced among artists who desperately wanted to learn and understand the human form. As Italian Renaissance artist and historian Giorgio Vasari explained, “…having seen human bodies dissected one knows how the bones lie, and the muscles and sinews, and all order of conditions of anatomy.”

Looking at Michelangelo’s Moses, for example, and we can admire the attention to detail, the realness of the muscles, and the humanity in his face. Yes, these figures were meant to be spiritually interpreted and adored, but they were also so real, and seemingly made of flesh and bone, that their faithful rendering created an even more awe-inspired reaction in those who viewed it. It can be said that in replicating man faithfully, these artists were also replicating the work of God, and that in itself is holy and worthy adulation.

The ancients, initiating this study and imitation of nature, most notably with their architecture, incorporated natural orders into their own religious experience. Within the architecture of their temples and mausoleums, they mimicked the symmetry and balance found in the natural world around them. Nature, for them, was one in the same as the gods. In both antiquity and Renaissance Italy, natural orders and ratios are clearly championed. By studying and replicating nature, you are, in a sense, copying the divine, and what a holy experience that can be if you get it right – and to get it right, you need math and an understanding of design.

In Renaissance works like the Tempietto, we see exactly that. Architects like Bramante were surrounded by the remains of ancient temples, able to study in person what books like Vitruvius’ De architectura laid out as the principles and ideals of balance and harmony. In these ancient temples resided the math of ratios and perspective, as well as a tangible harmony between structure and space. While the ancients invented the balance and homogenization of an entire space, the Renaissance arguably perfected it, and found a spiritual grounding in doing so. As a visitor (or worshiper, or pilgrim, or tourist) inhabiting a space like the Tempietto, there is a sense of wonder and peace. You are surrounded by beauty and harmony. In harmony, there is perfection, and in perfection there is godliness.

Tempietto Details

Let’s highlight some of the more technical aspects of the Tempietto that show off all this aforementioned harmony and balance. Most obvious and significant is that the structure itself is radial (circular) in shape, as opposed to a crucifix form that we often find in Christian religious spaces (i.e. just about every church in Italy). The colonnade of the temple is composed of sixteen columns fashioned in the Tuscan order (a simpler Doric style), supporting an exceptional homage to classical architecture in the form of triglyphs and metopes in its frieze. The metopes depict papal symbols and items used in prayer (such as the crossed keys of St. Peter). One-to-one and one-to-two ratios govern a number of the Tempietto’s dimensions, and the drum and the dome are of equal height. The interior of the Tempietto is only about 14 ½ feet, suggesting it was intended to be seen and admired, and not to function as a church holding worshipers.

The design of a temple depends on symmetry, the principles of which must be most carefully observed by the architect. They are due to proportion, in Greek ἁναλογἱα. Proportion is a correspondence among the measures of an entire work, and of the whole to a certain part selected as standard. From this result are the principles of symmetry. Without symmetry and proportion there can be no principles in design of any temple.

Vitruvius, De architectura, Book I

At the same time he was constructing this miniature masterpiece, Bramante was putting his architectural chops to test on a much bigger project related to the same saint: the rebuilding of Saint Peter’s Basilica, the largest church in the world. But to me, the Tempietto is as worthy of awe and admiration, and despite its petite stature, it still absorbs the visitor and provides an experience that distinguishes architecture from other art forms. Architecture, in a sense, is more of an experiential medium – it doesn’t just ask to be seen, it envelops you and asks to be felt.

You can visit Bramante’s Tempietto through the entrance of the Spanish Royal Academy in the Trastevere neighborhood of Rome. It’s open every day except Monday, from 10am – 6pm.